|

| The Full Crash |

Capturing the Crash : Surf Stacking

I don't get to the shore as often as I would like. Those

of us who live around Keene New Hampshire are proud of announcing that we are

located in the “precise geographic  center of New England”, but that does mean

that I must make a long trek to get to the ocean. I grew up on the north

shore of Boston and spent my summers on the water in Gloucester Massachusetts.

I love living in the Monadnock region but my distance from the shore is

my only major regret, so, whenever I get the chance, I bring my camera to

capture the restless water. From my sadly limited experience, I can't

claim to be an expert on ocean surf photography, but, since I seldom can wait for

the perfect conditions, I have learned something about making the best of the

conditions with which I am presented.

center of New England”, but that does mean

that I must make a long trek to get to the ocean. I grew up on the north

shore of Boston and spent my summers on the water in Gloucester Massachusetts.

I love living in the Monadnock region but my distance from the shore is

my only major regret, so, whenever I get the chance, I bring my camera to

capture the restless water. From my sadly limited experience, I can't

claim to be an expert on ocean surf photography, but, since I seldom can wait for

the perfect conditions, I have learned something about making the best of the

conditions with which I am presented.

center of New England”, but that does mean

that I must make a long trek to get to the ocean. I grew up on the north

shore of Boston and spent my summers on the water in Gloucester Massachusetts.

I love living in the Monadnock region but my distance from the shore is

my only major regret, so, whenever I get the chance, I bring my camera to

capture the restless water. From my sadly limited experience, I can't

claim to be an expert on ocean surf photography, but, since I seldom can wait for

the perfect conditions, I have learned something about making the best of the

conditions with which I am presented.

center of New England”, but that does mean

that I must make a long trek to get to the ocean. I grew up on the north

shore of Boston and spent my summers on the water in Gloucester Massachusetts.

I love living in the Monadnock region but my distance from the shore is

my only major regret, so, whenever I get the chance, I bring my camera to

capture the restless water. From my sadly limited experience, I can't

claim to be an expert on ocean surf photography, but, since I seldom can wait for

the perfect conditions, I have learned something about making the best of the

conditions with which I am presented. Last weekend Susan I traveled to visit old friends who are now

living in York Maine. We were excited to spend time with Wally and Michele

and even more excited to see their new granddaughter Maya and her doting

parents, Emile and Keri. Of course I also had my eye on the weather and

tides to see what I might capture by sneaking away to the shore. York's

premiere coastal attraction is the classic Nubble Lighthouse perched

dramatically on its tiny island off Cape Neddick. I've shot the

lighthouse many times but I am always looking for new light and angles.

On this trip I had to work a little harder.

Last weekend Susan I traveled to visit old friends who are now

living in York Maine. We were excited to spend time with Wally and Michele

and even more excited to see their new granddaughter Maya and her doting

parents, Emile and Keri. Of course I also had my eye on the weather and

tides to see what I might capture by sneaking away to the shore. York's

premiere coastal attraction is the classic Nubble Lighthouse perched

dramatically on its tiny island off Cape Neddick. I've shot the

lighthouse many times but I am always looking for new light and angles.

On this trip I had to work a little harder.  |

| Nubble Light, A Better Dawn |

I initially planned to get up early on Sunday for sunrise at the light, but, as I went to bed, my iPad showed me that the morning was predicted to heavily overcast. No chance for a glorious sunrise and besides the tide would be nearly dead low at dawn. There seemed nothing to be gained from dragging myself out of bed at 4AM. I only half reluctantly turned off my alarm and settled in for a nice long rest. My next option was to get up for a leisurely breakfast with friends and then see how things looked at around noon when the tide would be high and perhaps there would be a few breaks in the clouds.

Of course even on an overcast day Nubble Light is a popular

tourist attraction and the dense noontime crowd was assembled on our arrival.

Fortunately, the tourist thin substantially down on the slippery rocks

and I was able to find a number of unobstructed angle to the lighthouse.

The decent was a bit scary considering my crumby left hip, which is scheduled

for replacement next month, but I made it down without damage to either my joints

or, more importantly, to my gear.

I hoped for energetic surf from the passing storm, but

the waves were only moderate. I scouted for locations with interesting

foreground rocks and a good angle on the light, and then the trick was to

get low on the rocks to minimize the apparent gap between the shore and the

island. I settled in and, as my butt became progressively cold and damp,

I planned the shots I would need to capture the full drama of the crashing

surf.

I hoped for energetic surf from the passing storm, but

the waves were only moderate. I scouted for locations with interesting

foreground rocks and a good angle on the light, and then the trick was to

get low on the rocks to minimize the apparent gap between the shore and the

island. I settled in and, as my butt became progressively cold and damp,

I planned the shots I would need to capture the full drama of the crashing

surf.

The challenge of surf photography comes as we try to capture

the sense of relentless motion within the limitations of a still image.

Here are the problems, and some of my attempts at solutions.

Surf in Motion

|

| Newport Dawn, 1/250th f18 |

The portrayal of surf varies widely primarily based on the

length of the shutter. Short exposures freeze the drops in mid-flight

highlighting the hectic, random nature of the splash, but I love long exposures

that render the water in a soft blur that portrays a sense of motion.

|

| Portland Light Surf, 1/4 f22 |

For these images the timing can be quit

critical. With longer exposures the detail in the water can be lost and

with exposures of several seconds the churning ocean can be rendered as a misty

flat pool. It is all a matter of artistic taste, but, in most situations,

I prefer shutters set to less than a second to preserve enough detail in the

water to reflect the patterns in the flow.

|

| Penobscot Mist , 2 Seconds f22 Flattens the Waves |

Capturing the Right Wave

|

| Wave Patterns |

|

| Pemaquid Light, One of 35, 1/6th f22 |

photography and large

memory cards. Years ago I was shooting the surf off of Pemaquid Light in Maine

from a precarious rock which projected into the bay. Before I was nearly washed

away I managed to capture more than seventy images, as I tried to anticipate

the perfect wave. At home I was thrilled to find two images from the 70

that I felt were worthy "keepers".

One is thirty-five is not a bad ratio.

Getting Depth

I usually try to include interesting foreground rocks in my surf

and lighthouse images and, even with the small apertures dictated by my long

exposures, it is often impossible to capture the full depth of field in focus.

I routinely use focus stacking to get everything sharp but the foreground

surf has a tendency to get in the way.

|

| Getting the Full Crash |

On a number of the photographs of

Nubble Light, I first shot a series of images focused on various planes,

restricting my shots to times when the surf was quiet. I combined these in

a “Focus Stack” using Photoshop's Auto Align and Auto Blend tools and used this

blend as my baseline full focus image. I then settled back, focused on

the foreground rocks, and shot multiple images of the crashing surf trying to

capture the perfect wave and its aftermath. In post I was able to choose

among my best surf shots to blend with my baseline depth of field image.

Cool huh? Cheating? Of course not it was what I saw - almost

- there is still one more step to blend the entire experience into a single

image.

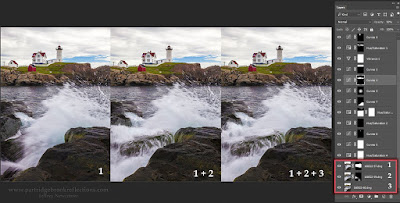

Capturing the Whole Event : Surf Stacking

|

| After the Storm , Kennebunkport Maine |

When I watch a wave crashing against the rocks the full

dramatic event usually takes a second or two from the initial explosion of surf

through the secondary surge of froth blanketing the rocks. It is much

like fireworks whose initial explosion is followed by the flowering of colored

streamers. For both fireworks and crashing surf, my eye records the event

as an unbroken continuum, but, given my desired shutter speed, a single still

photograph of surf can only record a portion of the display.

|

| Three Part Splash |

Returning to the crash, I blended parts of three shots taken to record the progression of the wave's “performance”.

The first shot captured the splash at its peak but tended to wipe out the view of the rocks further in. The second and third shots combined to show the surf working its way around the rocks revealing subtler patterns of dark and light. Using the blend of the three shots, I was able to much more closely match, in a single digital image, what my miraculous "analog" eye perceived.

Shooting the Slot

I finished by settling into a somewhat precarious position along the

slippery edge of a slot that faced the lighthouse. Again, a burst of

images recording a single wave includes views of initial splash along with the

rushing swirl that shot up the slot. I just had to remember to lift my

feet with each surge. No single image

recorded the full cascading event but a blend of three images was much truer to

what was dramatically apparent to the eye. I then added this surf blend

to a background image which was captured to get the lighthouse in sharp focus.

I finished by settling into a somewhat precarious position along the

slippery edge of a slot that faced the lighthouse. Again, a burst of

images recording a single wave includes views of initial splash along with the

rushing swirl that shot up the slot. I just had to remember to lift my

feet with each surge. No single image

recorded the full cascading event but a blend of three images was much truer to

what was dramatically apparent to the eye. I then added this surf blend

to a background image which was captured to get the lighthouse in sharp focus. |

| The Slot |

The Purist Lament

Ok, while you are busy being appalled with all my trickery and

before you say that I was not recording the actual experience, I would argue

that the least accurate representation of crashing surf would be a single image

freezing only a short segment of the event. Whether or not you agree

there is one more point me can all acknowledge.

Don't Get Washed Out to Sea

|

| Almost Stranded Off Hampton Beach NH |

I hope that you will find better conditions on your next trip to the shore. The best opportunities generally come at high tide after a big storm has kicked up massive breakers, but with a little planning you should be able to make the most out of whatever nature provides. The waves are giving their all to the performance, the least you can do is work to bring it all home.

Jeffrey Newcomer