|

My Lightroom Catalog

Actually, Melk Abbey Library, Austria |

I’ve

just finished my Introduction to Adobe Lightroom Class. This was

the fourth time I have offered the course and I have found two important themes

that have been consistent throughout each of the sessions.

First

I am amazed how much I learn each time I prepare the material for the classes.

My students always seem to come up with questions that challenge my own

understanding of this remarkably capable program, and I am invariably

stimulated to come up with refinements of my explanations. Perhaps, at some

point, I will get it all right, but then it will be time to move on to

something else.

First

I am amazed how much I learn each time I prepare the material for the classes.

My students always seem to come up with questions that challenge my own

understanding of this remarkably capable program, and I am invariably

stimulated to come up with refinements of my explanations. Perhaps, at some

point, I will get it all right, but then it will be time to move on to

something else.

The

other persistant issue that seems to come out of every class is the

confusion over the functions of the Lightroom Catalog. This is so

essential for the understanding of how Lightroom works  that I spend much of my

first two hour class discussing the topic, and yet the misunderstandings always

seem to linger. Mostly, it must be my fault, but I think sometimes the students

are so excited to get to the “sexy” parts, especially the powerful editing

functions, that they blow right past the boring nuts and bolts of how the

program actually works. At the end of this last class I asked everyone to

suggest topics that could have benefited from greater emphasis and it all

seemed to come down to the care and feeding of the Lightroom Catalog. It

was only after they had manipulated some images, tried to understand where

those changes were to be found, and how to translate them to actual flesh and

blood image files, that they appreciated the importance of that obscure

catalog.

that I spend much of my

first two hour class discussing the topic, and yet the misunderstandings always

seem to linger. Mostly, it must be my fault, but I think sometimes the students

are so excited to get to the “sexy” parts, especially the powerful editing

functions, that they blow right past the boring nuts and bolts of how the

program actually works. At the end of this last class I asked everyone to

suggest topics that could have benefited from greater emphasis and it all

seemed to come down to the care and feeding of the Lightroom Catalog. It

was only after they had manipulated some images, tried to understand where

those changes were to be found, and how to translate them to actual flesh and

blood image files, that they appreciated the importance of that obscure

catalog.

I’ll

try to spend more time on the catalog in my next class, but here is another run

at a few questions that might help to clarify what the Lightroom catalog is,

and perhaps more importantly, what it is not.

Where do

Image Files Go When they are Imported to Lightroom

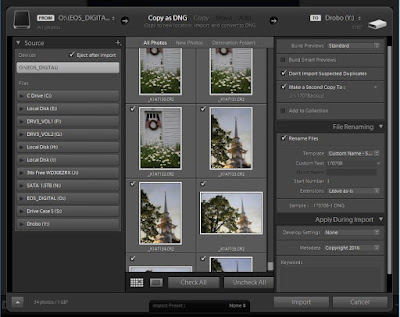

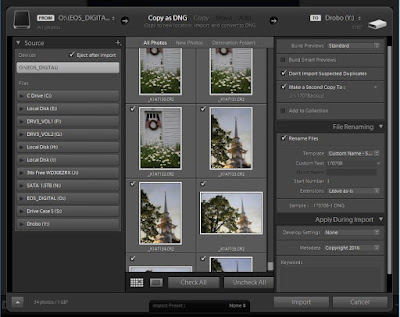

The

first problem is the word “Import”. Import suggests that the image files

are physically added to Lightroom and this is never true. When images are

imported, it is only information about the files that is stored in the

Lightroom Catalog. Rather than “Import”, a better term might be “Referenced”

since the original image file is not moved or altered. Lightroom’s import

process only involves “telling” the program essential pieces of information about the files, such as that the files exist, where they

are located, and how they have been edited in the program. This is

easier to understand when Lightroom is importing information about images that

are already on the computer, but confusion can occur when the files are being

uploaded to the computer from memory cards. Lightroom provides a convenient

mechanism to import file information

into the Lightroom Catalog, at the same time that image files are being uploaded to the computer, but it is important

to understand the difference between uploading the physical image file and

importing the file information to the Catalog. Careful study of this overly busy flow diagram may be helpful in separating the two processes.

The

first problem is the word “Import”. Import suggests that the image files

are physically added to Lightroom and this is never true. When images are

imported, it is only information about the files that is stored in the

Lightroom Catalog. Rather than “Import”, a better term might be “Referenced”

since the original image file is not moved or altered. Lightroom’s import

process only involves “telling” the program essential pieces of information about the files, such as that the files exist, where they

are located, and how they have been edited in the program. This is

easier to understand when Lightroom is importing information about images that

are already on the computer, but confusion can occur when the files are being

uploaded to the computer from memory cards. Lightroom provides a convenient

mechanism to import file information

into the Lightroom Catalog, at the same time that image files are being uploaded to the computer, but it is important

to understand the difference between uploading the physical image file and

importing the file information to the Catalog. Careful study of this overly busy flow diagram may be helpful in separating the two processes.

The

Database Advantage

Unlike

Adobe Bridge, Lightroom is not a file based management system. Lightroom

is a database, that keeps track of information about each image file. For

each image, the program registers only four pieces of information:

- A set

of previews used to display and manipulate the image

- A list

of all the editing that's has been applied from within Lightroom

- The

Metadata recorded within the file

- The

physical location of the file in the computer

|

| Contents of Lightroom Catalog Directory |

- Catalog Data: [catalog name].lrcat

- Image Previews: [catalog name] Previews.lrdata

- Smart Previews (Lightroom 5 and later): [catalog

name] Smart Previews.lrdata

Because

Lightroom is a database, which manipulates relatively short text files, it can

perform tasks, such as searching and sorting, much more quickly than file based

programs, such as Adobe Bridge. This becomes more important when dealing with

a large or scattered library. When my own image library exceeded 400,000

pictures, Bridge became impractically cumbersome, and to take advantage of the

efficiency of the database model, I finally made the jump to Lightroom.

Because

Lightroom is a database, which manipulates relatively short text files, it can

perform tasks, such as searching and sorting, much more quickly than file based

programs, such as Adobe Bridge. This becomes more important when dealing with

a large or scattered library. When my own image library exceeded 400,000

pictures, Bridge became impractically cumbersome, and to take advantage of the

efficiency of the database model, I finally made the jump to Lightroom.

I can't resist pointing out that, although Melk Abbey's ancient library contains about 100,000 manuscripts, incunabula (printed works before 1500), and books, my catalog has over 400k files, of course of slightly less antiquity.

Keep

it in Lightroom : A Disadvantage

As

an image management program, Lightroom is amazing, but it  does have

disadvantages. Because Lightroom

manipulates information about the images and not the image files themselves, it requires more care with the movement of

files. It is important to establish the habit of only moving files from

within Lightroom. In one sense, Lightroom doesn’t “know” where an image

file is, it only knows where we have told it that it is located. Files

that are moved outside of Lightroom will be lost to the program, generating the

dreaded "!" flag on the files, and "?" marking their directories. These orphans can be found and re-registered, but, a lot of

pain can be avoided by following the “Keep

it all in Lightroom” mantra.

does have

disadvantages. Because Lightroom

manipulates information about the images and not the image files themselves, it requires more care with the movement of

files. It is important to establish the habit of only moving files from

within Lightroom. In one sense, Lightroom doesn’t “know” where an image

file is, it only knows where we have told it that it is located. Files

that are moved outside of Lightroom will be lost to the program, generating the

dreaded "!" flag on the files, and "?" marking their directories. These orphans can be found and re-registered, but, a lot of

pain can be avoided by following the “Keep

it all in Lightroom” mantra.

|

| Found It : Catabane Falls, Now gone |

Where is the

Lightroom Catalog?

The

Lightroom Catalog is stored in a directory that can be located anywhere in the

computer, but, by default, is found at:

Windows:

\Users\[user name]\Pictures\Lightroom

Mac OS:

/Users/[user name]/Pictures/Lightroom

If

it is in a different location, it can be found in the Catalog Settings of the

Lightroom Preferences.

If

it is in a different location, it can be found in the Catalog Settings of the

Lightroom Preferences.

You

can have as many catalogs as you wish. Some photographers keep separate

catalogs for work and personal images, but without a compelling reason to

compartmentalize your work, a single catalog may be a simpler option.

What Happens

when I Edit Images in Lightroom

|

| Image Edited in Lightroom |

The

essential thing to understand is that all editing in Lightroom is

nondestructive. Repeat after me, “Nondestructive”.

Changes that are made during editing are applied to the preview image in

Lightroom, but not to the actual physical images.

|

Actual image is not altered on the drive while

Lightroom Adjustments STAY in Lightroom |

These changes can be

thought of a series of instructions that are saved with the image information

in the Lightroom Catalog. They affect the appearance of the preview image

but are not applied to the pixels of an actual image until the

file leaves

Lightroom. Stepping out of Lightroom occurs when editing switches to an

external editor, such as Photoshop, or when the image is“Exported” to a physical file format, such as jpg, tif or psd. This also occurs when

images are shared such as in books, web pages or on social media.

|

| Export Dialog, Leaving Lightroom |

The key point

is that all the editing changes you make are simply a set of instructions that

don’t get applied until the image ventures from the warm safety of Lightroom into

the dark, pixel based, world, and even then the original Raw file stays intact.

That is why there is no “Save” command in Lightroom.

|

Wall's End, Guilford Vermont,

Final image with Lightroom Adjustments Exported the file |

The Nondestructive Life

I

hope this discussions has helped clarify some of the confusion about Lightroom

Catalogs. The more I try to simplify, the more complex it seems to get.

I have not covered many related topics such as how to move, combine,

rename, back-up or delete catalogs. This could be a topic for a future

blog, but all of these details are clarified in numerous articles on the web.

Summing Up

The

essential thing to understand is that Lightroom is a database program used to

keep track of images on your computer.

When

you edit photos, rate them, add keywords to them, or make other changes, as long

as you are in Lightroom, the changes are stored in the catalog, but

the photo files themselves are never touched.

Don’t

you wish life was like this. Try anything you want, take any risk, make

disastrous mistakes, and it is ALL “nondestructive”. When you finally

like the results just press “Export”.

Don’t

you wish life was like this. Try anything you want, take any risk, make

disastrous mistakes, and it is ALL “nondestructive”. When you finally

like the results just press “Export”.

The camera is light, with a

small sensor, but has a 24-1200mm fixed lens! With that focal length

range, why would you need other lenses? Susan and I tend to choose different

hikes on our tours. I generally stay with the photographers, making

frequent stops for shots, while Susan moves more quickly with the non-photographers,

who are often called the “natural history” groups. Since we are usually

exploring different areas, I assumed Susan would want her own camera to capture

the action, especially if she is the lucky one to be charged by the angry grizzly.

The camera is light, with a

small sensor, but has a 24-1200mm fixed lens! With that focal length

range, why would you need other lenses? Susan and I tend to choose different

hikes on our tours. I generally stay with the photographers, making

frequent stops for shots, while Susan moves more quickly with the non-photographers,

who are often called the “natural history” groups. Since we are usually

exploring different areas, I assumed Susan would want her own camera to capture

the action, especially if she is the lucky one to be charged by the angry grizzly.  The camera is light, with a

small sensor, but has a 24-1200mm fixed lens! With that focal length

range, why would you need other lenses? Susan and I tend to choose different

hikes on our tours. I generally stay with the photographers, making

frequent stops for shots, while Susan moves more quickly with the non-photographers,

who are often called the “natural history” groups. Since we are usually

exploring different areas, I assumed Susan would want her own camera to capture

the action, especially if she is the lucky one to be charged by the angry grizzly.

The camera is light, with a

small sensor, but has a 24-1200mm fixed lens! With that focal length

range, why would you need other lenses? Susan and I tend to choose different

hikes on our tours. I generally stay with the photographers, making

frequent stops for shots, while Susan moves more quickly with the non-photographers,

who are often called the “natural history” groups. Since we are usually

exploring different areas, I assumed Susan would want her own camera to capture

the action, especially if she is the lucky one to be charged by the angry grizzly.

Sorry for that unfortunately long

diversion, but I had to get it off my chest. The bottom line is that I

have a nice little camera to bring to athletic events such as the Red Sox, or

to third world countries where a big “fancy” camera could be a dangerous

attraction. Obviously, the 1200mm focal length on the SX50 HS allows me to get

closer to the action, but the camera also has a full range of controls, and

although the small sensor can show problems with noise at high ISOs, it does

result in a deep depth of field in macro images. And, perhaps most importantly,

the camera shoots in RAW!

Sorry for that unfortunately long

diversion, but I had to get it off my chest. The bottom line is that I

have a nice little camera to bring to athletic events such as the Red Sox, or

to third world countries where a big “fancy” camera could be a dangerous

attraction. Obviously, the 1200mm focal length on the SX50 HS allows me to get

closer to the action, but the camera also has a full range of controls, and

although the small sensor can show problems with noise at high ISOs, it does

result in a deep depth of field in macro images. And, perhaps most importantly,

the camera shoots in RAW!

Capturing action shots from far back

in the stands can be a challenge. Obviously, a long lens can be helpful,

but anticipating the key moments is difficult. Your arms can get numb

continually holding the camera in front of your face waiting for the magic to

happen. As much as I would love to capture the critical play, I don’t want to spend

the whole game with a camera blocking my view of the live action. I

usually shoot in just a few situations. Catching the swings is fairly easy.

Of course, being along the right field line I could only catch the

right-handlers. Capturing the quick and unpredictable action in the

infield can be difficult, but with a man on first I can watch for a steal or a

dive back to first to avoid a pick-off. If I am on the left field side I

can look for action in the home dugout. A little scratching or spitting

is

Capturing action shots from far back

in the stands can be a challenge. Obviously, a long lens can be helpful,

but anticipating the key moments is difficult. Your arms can get numb

continually holding the camera in front of your face waiting for the magic to

happen. As much as I would love to capture the critical play, I don’t want to spend

the whole game with a camera blocking my view of the live action. I

usually shoot in just a few situations. Catching the swings is fairly easy.

Of course, being along the right field line I could only catch the

right-handlers. Capturing the quick and unpredictable action in the

infield can be difficult, but with a man on first I can watch for a steal or a

dive back to first to avoid a pick-off. If I am on the left field side I

can look for action in the home dugout. A little scratching or spitting

is  always exciting. All of this needs to be limited within

reason. There are professional sports photographers right on the

sidelines who I can trusted to shoot the key plays. I just try to get a few

images to document my attendance at the event and settle back to finish my

popcorn. After all, I’m a landscape photographer and despite years of

visiting Fenway I have yet to see a tree in the “park”.

always exciting. All of this needs to be limited within

reason. There are professional sports photographers right on the

sidelines who I can trusted to shoot the key plays. I just try to get a few

images to document my attendance at the event and settle back to finish my

popcorn. After all, I’m a landscape photographer and despite years of

visiting Fenway I have yet to see a tree in the “park”.